Molluscum Contagiosum

By Courtney McClurkin, DPM; Andrew Olson, DPM

Molluscum contagiosum can be confused with a variety of different skin pathologies

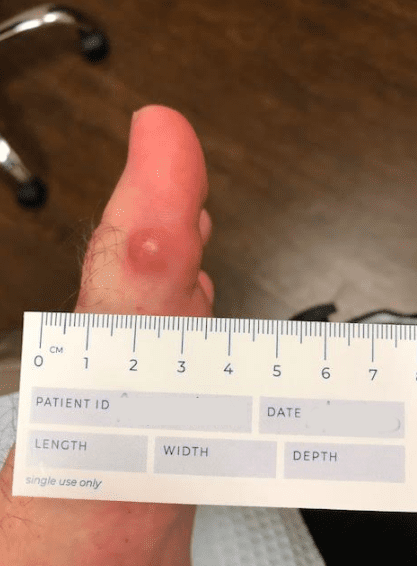

History

A 25 year old male with no known significant past medical history presents with a pigmented lesion to plantar aspect of his left foot present for an undetermined period of time.

Physical Examination

A raised red and black 3mm lesion is seen on the plantar aspect of left foot.

Diagnostic Testing

A 2mm punch biopsy was performed with clinical concern to rule out melanoma.

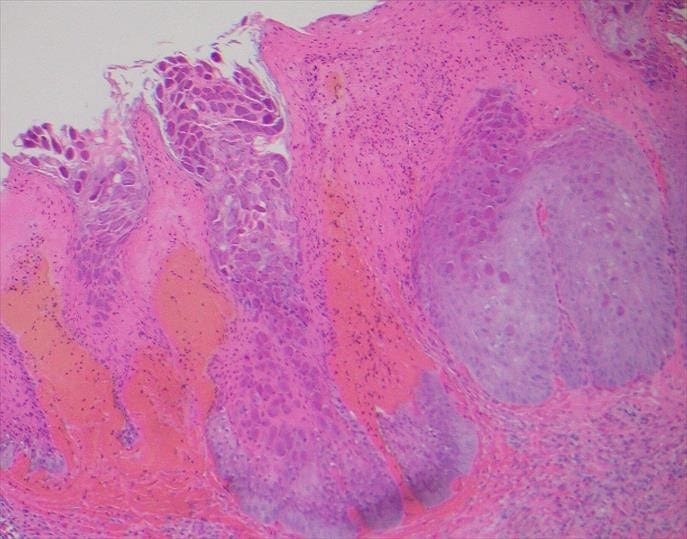

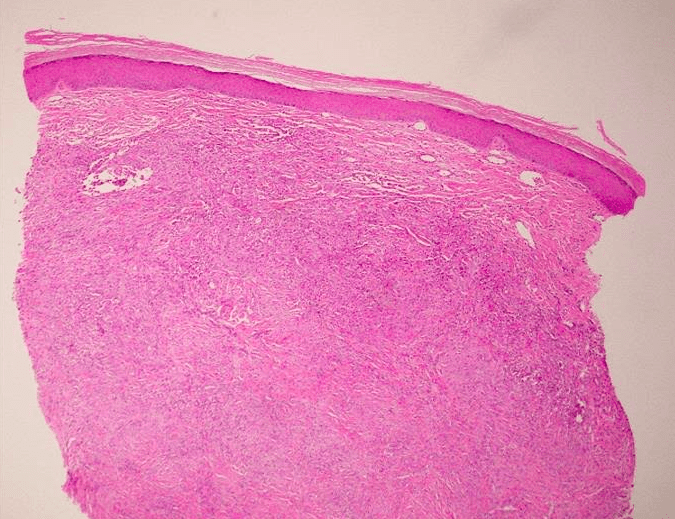

Histological Findings

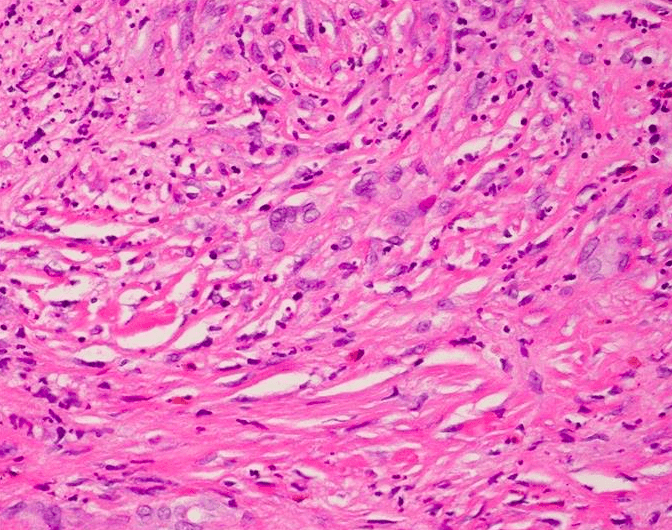

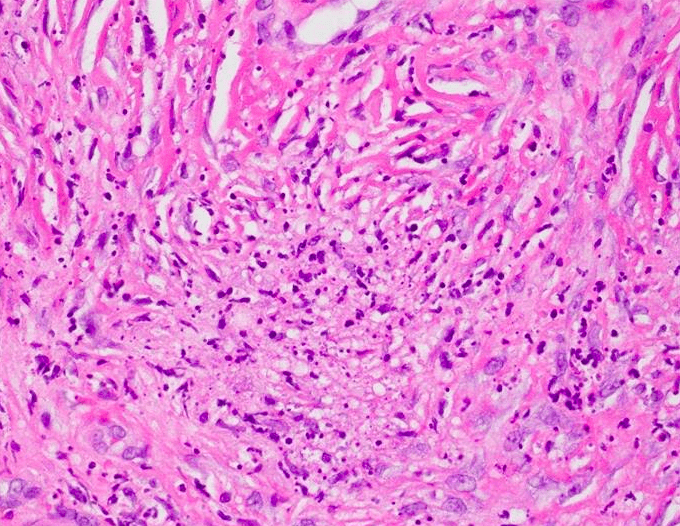

Typical histological features of molluscum contagiosum were identified including molluscum bodies, which are intracytoplasmic eosinophilic structures contained within epidermal cells. These molluscum bodies become basophilic in the upper part of the epidermis, and are found in high numbers in the horny layer. There is also a dense polymorphonuclear infiltrate noted adjacent to the epithelium containing the molluscum bodies.

Diagnosis

Molluscum contagiosum

Discussion

Molluscum contagiosum is a skin infection that is caused by a poxvirus. Transmission of the molluscum contagiosum virus is through contact with an infected person or contaminated surface. It is most commonly found in young children, but is also notorious for sexual transmission among adults and adolescents. Transmission rates are generally similar for the immunocompromised. However, the lesions can be more numerous, appear in atypical locations, and be more resistant to treatment. The virus incubates for a period of 14 days to 6 months, followed by formation of slowly enlarging, single or multiple lesions. The lesions most commonly appear as pearly, umbilicated papules. They can become inflamed and erythematous, causing a “molluscum dermatitis”. Most cases are self-limiting, though crops of lesions may come and go over the span of months. There are, however, a plethora of treatment options ranging from physical destruction to systemic treatments.

Clinically, molluscum contagiosum can be confused with a variety of different skin pathologies, including but not limited to: verruca vulgaris, condyloma, nevocellular nevus, basal cell carcinoma, keratoacanthoma, lichen planus, eczema, foreign body granuloma, sarcoidosis, folliculitis, and true epidermal cyst.

Two histologic variants exist. The pseudocystic variant is distinguished by invagination of colonized epithelium of dilated horn-filled infundibula bordered by a thick epidermis and are filled with compact, thick keratin. In the polyploid variant, the dermis located beneath molluscum contagiosum has loose collagen fibers, dilated vessels, and inflammatory infiltrate. Molluscum bodies are the most distinguishing histologic feature. These are large cells with cytoplasmic eosinophilic inclusions that contain viral particles.

Associated lesions with molluscum contagiosum are common, including true epidermal cysts, nevocellular nevus, Unna nevus, Clark nevus, soft fibromas, and Kaposi sarcoma. Abscesses can be associated due to discharge of molluscum bodies to the dermis, followed by release of proinflammatory cytokines and activation of complement pathway.

Treatment

While molluscum contagiosum is typically self-limiting within 6 months, there are treatment options available. Treatment is initiated in order to alleviate discomfort produced by itchy or painful lesions, for cosmetic reasons, to prevent spread of lesions, as well as to prevent trauma, scarring, and secondary infection of lesions.

Surgical treatments include: cryotherapy, curettage, punch biopsy, manual excision, electric cauterization, and laser therapy.

Topical treatments include: acidified nitrite, adapalene, Australian lemon myrtle oil, benzoyl peroxide, bromogeramine, cantharidin, cidofovir, diphencyprone, griseofulvin, honey, hydrogen peroxide, imiquimod, iodine, phenol, podophylotoxin (HIV patients), potassium hydroxide, salicylic acid, tea tree oil, and tretinoin.

Systemic treatments include cimetidine, griseofulvin, and cidofovir (in HIV-infected patients).

References:

Cribier, B., Y. Scrivener, and E. Grosshans. Molluscum contagiosum: histologic patterns and associated lesions. The American Journal of Dermatopathology 23(2): 99-103 (2001).

Mancini, A.J. and A. Shani-Adir. Other Viral Diseases. Dermatology 3rd ed. (2012): p. 1358-59.

Van der Wouden, J.C., et. al. Interventions for cutaneous molluscum contagiosum (review). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews Issue 5, Art. No.: CD004767 (2017).