Onychomycosis

Case study

By Steven Goldstein, DPM; Basem Halaka, DPM; David Vance, DPM; Jason Weslosky, DPM

History of Present Illness

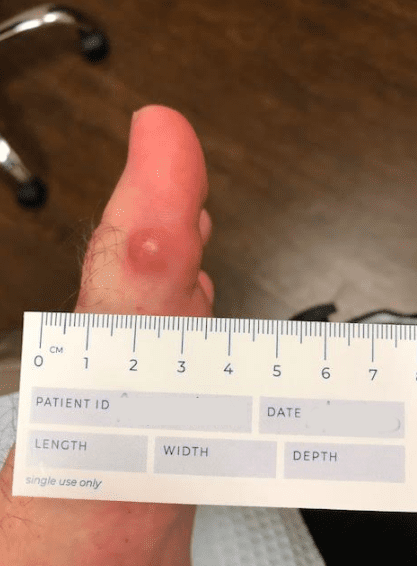

The patient is a 62 year old male with a 2 year history of thickened, elongated, and yellow discolored nails of the hallux bilateral. The nails appear dystrophic with evidence of subungual debris. The patient does not recall any significant trauma to the nails but does admit to uncomfortable rubbing of the bilateral hallux nails in his shoes. The patient does not have any other contributing medical history.

Differential Diagnosis

Diagnostic considerations in this case include onychomycosis, trauma, psoriasis, lichen planus, chronic paronychia, and dermatitis.

Work-up

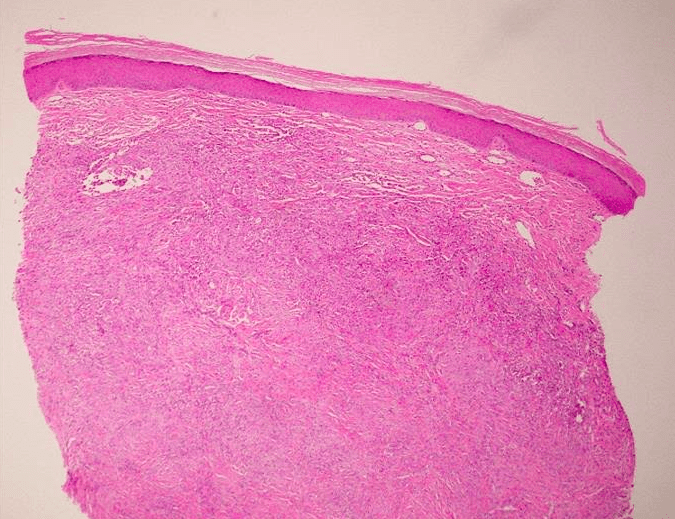

The bilateral nails were debrided and multiple keratogenous samples were sent for analysis (histopathology and PCR). Care was taken to remove debri subungually as well as portions of the proximal nail plate.

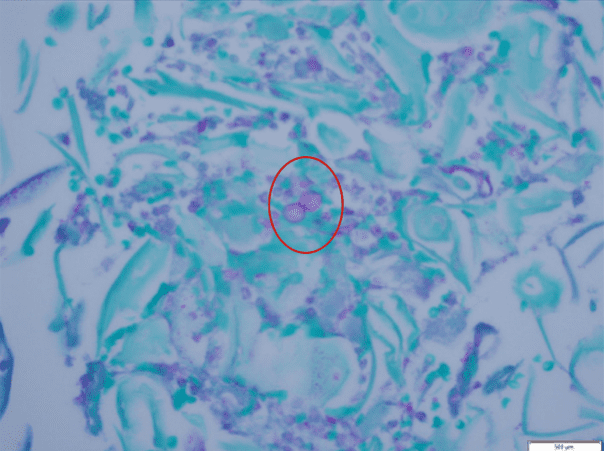

Histopathology and Molecular Analysis

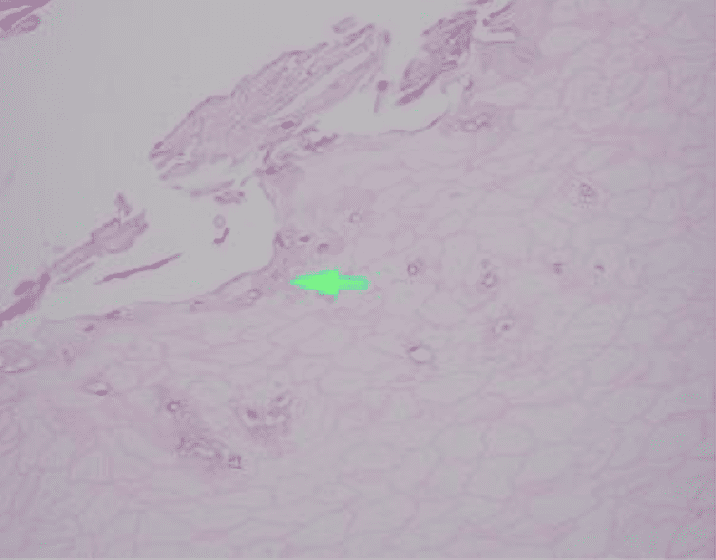

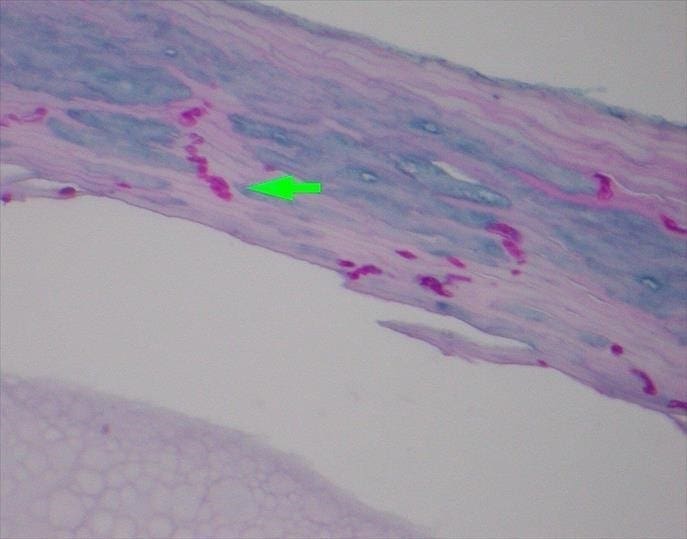

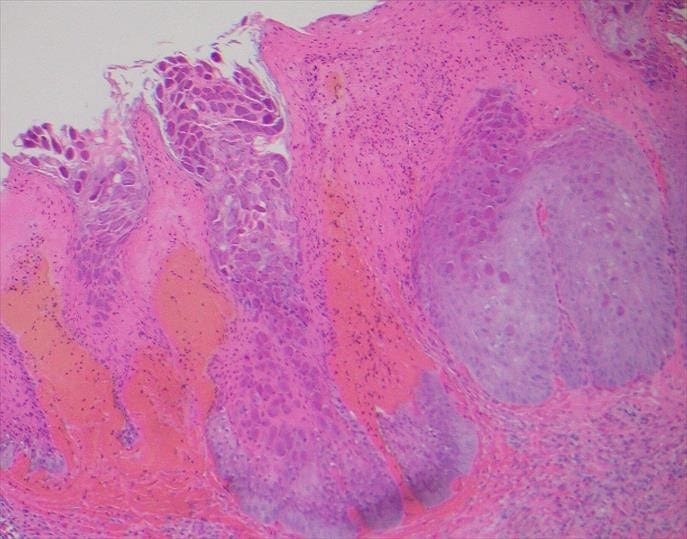

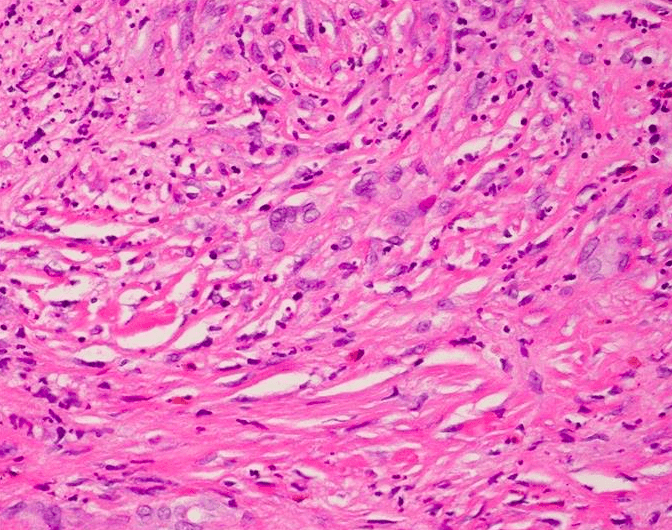

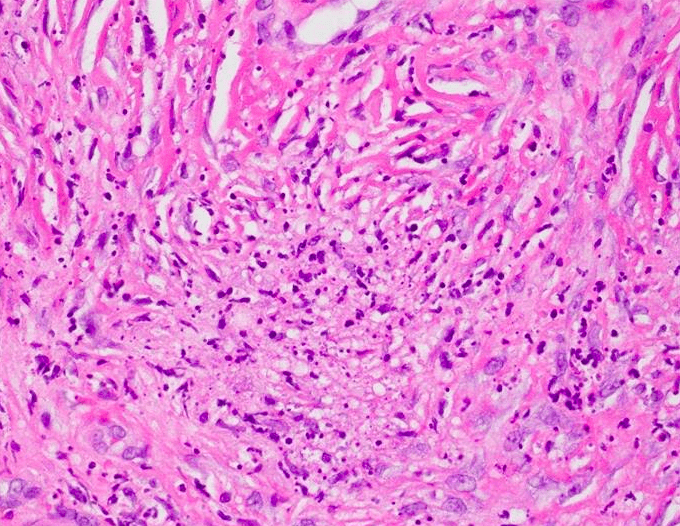

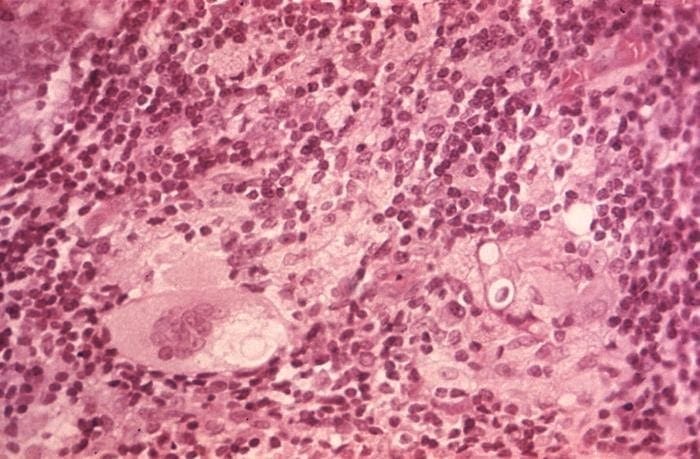

Identified in this study were histopathologic features of acute and chronic micro-trauma as well as onychomycosis. Fungal elements were demonstrated with both PAS and GMS stains. Fontana Masson staining was performed as well and was negative for melanin. PCR testing was performed and was able to identify the organism, a saprophyte of the Fusarium genus.

Discussion

The most prevalent risk factor for developing onychomycosis is advanced age. Other risk factors include warm climate, peripheral vascular disease, and diabetes mellitus. Immunocompromised conditions are also thought to be linked to the prevalence of onychomycosis, especially those caused by non-dermatophyte species. It should also be noted that onychomycosis and nail trauma often coexist, with nail trauma often being a predisposing factor for the development of onychomycosis.

While many onychomycosis cases are caused by dermatophytes, it is important to note that there are also cases involving yeasts and saprophytic species, thus proper identification is key to appropriate treatment . In this case, the isolated pathogen was a saphrophyte of the Fusarium genus. The most opportunistic of this species include F. solani complex, F. oxsporum complex and F. fujikorai complex. Most commonly these species cause onychomycosis in tropical countries however they are also present in temperate and artic climates with recent reports of Fusarium as a common pathogen in central European countries.

Treatment

Multiple treatment options exist for onychomycosis. Medications exist in both oral and topical forms. Furthermore other options for treatment such as mechanical and chemical avulsion exist. Topical treatments are often reserved for superficial white onychomycosis or distal subungual onychomycosis affecting less than 50 percent of the nail surface. Tolnaftate and Ciclopirox are common topical therapies employed. Topical urea may be used in conjunction with topical therapies to act as a vehicle to increase penetration of the medication into the nail unit. Oral treatment options are often a better option for proximal subungual onychomycosis or onychomycosis that is involving more than 50% of the nail plate. Terbinafine, Itraconazole, Fluconazole are all oral medication options for treating this condition. Terbinafine is perhaps the most commonly prescribed and is useful against both dermatophyte and some non-dermatophyte species. Itraconazole has greater effect toward non-dermatophyte species however it must be used with caution as it is contraindicated in pregnancy. Fluconazole is another option however therapeutic treatment times remain longer when compared to other oral medications. Speciation of the organism may guide to the most effective oral therapy for the specific organism. Furthermore, both mechanical and chemical debridement remain as options for treating onychomycosis. Chemical debridement often consists of applying a compound containing urea to the nail. Depending on the exact formulation of the compound, this may be done under occlusion or without occlusion. It should be noted that chemical debridement alone is not effective and often has to be combined with other treatment modalities. Lastly, mechanical debridement or avulsion of the nail plate remains a viable option especially in cases where previously mentioned treatment modalities have failed. However care must be taken in patients with comorbidities such as peripheral vascular disease, diabetes, or infection.

Laboratory Testing Modalities for Onychomycosis

There are multiple tests that can be performed to evaluate for the presence of fungi in a tissue specimen. Some of the commonly performed tests include the periodic acid-Schiff(PAS) reaction, Grocott methenamine silver(GMS) stain, Fontana-Masson stain, culture, and polymerase chain reaction(PCR) assay. PAS is a periodic acid and Schiff reagent stain. It is useful in detecting carbohydrates within the cell walls of living fungi. In PAS testing, the aldehyde groups in the fungal cell walls react with the stain to produce a magenta color. The GMS stain is a chromic acid and bisulfite stain. It is also useful in detecting fungal elements; however it is generally able to produce better staining contrast as well as improved detection of degenerated or dead fungi. The Fontana-Masson stain highlights melanin pigment in certain fungal organisms along with melanin pigment deposition in various conditions. Fontana-Masson has shown variable staining among different types of fungi; however, higher quantity staining within the fungal organisms favors dematiaceous fungi (pigmented saprophytic mold). Fungal culture can be performed on fresh tissue but suffers from long turn-around time (28 days) and high false negative results. PCR Assay detects the genetic material of fungi. Advantages of PCR include rapid (1-2 day) turn-around, a minimum of 25% higher sensitivity than culture, and the ability to identify the specific fungal species.

References:

Werner B, Antunes A. Microscopic examination of normal nail clippings. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2013;3(3):9-14. Published 2013 Jul 31.

Ranawaka RR, Nagahawatte A, Gunasekara TA. Fusarium onychomycosis: prevalence, clinical presentations, response to itraconazole and terbinafine pulse therapy, and 1-year follow up in nine cases. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54(11):1275-1282.

Rammlmair A, Muhlethaler K, Haneke E. Fusarium onychomycoses in Switzerland-A mycological and histopathological study. Mycoses. 2019;62(10):928-931.

Gupta AK, Simpson FC. New therapeutic options for onychomycosis. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2012;13:1131-1142.

Gupta AK, Kohli Y. In vitro susceptibility testing of ciclopirox,terbinafine, ketoconazole and itraconazole against dermatophytes and nondermatophytes, and in vitro evaluation of combination antifungalactivity. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:296-305.

Figueiredo VT, de Assis Santos D, Resende MA, et al. Identificationand in vitro antifungal susceptibility testing of 200 clinical isolates of Candida spp. responsible for fingernail infections. Mycopathologia. 2007;164:27-33.

Emam, Sherin, and Osama El-salam. “Real-Time PCR: a Rapid and Sensitive Method for Diagnosis of Dermatophyte Induced Onychomycosis, a Comparative Study.” Alexandria Journal of Medicine, 29 Aug. 2015.

D’Hue, Zandra, et al. “GMS Is Superior to PAS for Diagnosis of Onychomycosis.” Journal of Cutaneous Pathology, 14 Aug. 2007.

West, Kelly, et al. “Fontana-Masson Stain in Fungal Infections.” Dermatopathology, Dec. 2017.